In one of the opening scenes of Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, twin brothers Smoke and Stack—both played brilliantly by Michael B. Jordan—survey the Mississippi sawmill they’re about to transform into a blues juke joint. It’s 1932, and the brothers, returned from Chicago with questionable money and unquestionable style, envision a refuge where the town’s Black community can eat, drink, and dance to the blues. It’s a bold dream in Jim Crow-era America, ambitious enough without vampires showing up to the party. But show up they do, turning a soulful blues joint opening night into a supernatural showdown over music’s sacred power and sinister potential.

At first glance, vampires invading a Southern juke joint might read like horror-movie kitsch. But in Coogler’s hands, these aren’t your traditional monsters. Led by Jack O’Connell’s slippery, charismatic Remmick, the vampires crave more than blood—they seek to feed on the creative genius of the club’s rising blues star, Sammie Moore (an electrifying Miles Caton). Coogler leans heavily on the metaphor of appropriation here: these vampires, eerily seductive yet ultimately hollow, represent whiteness, commercial greed, and cultural exploitation. They’re the musical colonizers who drain originality from Black culture, leaving behind only pale imitations.

It’s heady, ambitious stuff, and if Coogler occasionally overstretches his allegory, his cinematic instincts ground the film firmly. “I wanted the movie to have the simplicity and the profound nature of a Delta blues song, but also the inevitability and escalating chaos of Metallica’s ‘One,’” Coogler told journalists ahead of the premiere. The influence of Metallica is not subtle: drummer Lars Ulrich’s urgent percussion punctuates Ludwig Göransson’s lush, hypnotic score, and the film’s narrative tension rises and falls like that song’s iconic crescendo. But Coogler doesn’t merely use Metallica as mood music—he borrows their structural ambition, allowing the film to evolve from a slow-burning historical drama into something frenetic and feverish.

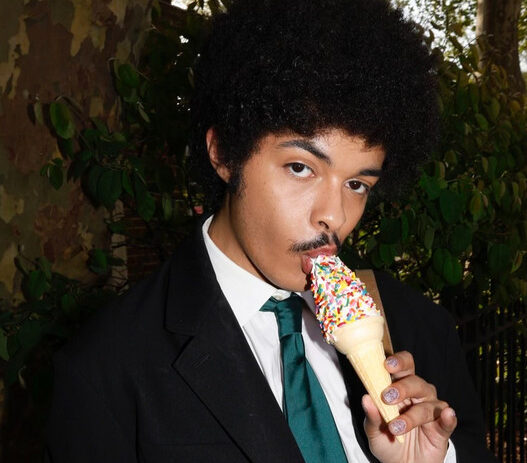

Sinners becomes most compelling in its musical set pieces. The centerpiece of the film—already hailed as one of the year’s great cinematic moments—is Sammie’s performance of “I Lied To You.” As Sammie plays, the camera pans through a supernatural vision: ghosts of musical past and future blend seamlessly into the club’s vibrant crowd, creating a visual metaphor of Black musical legacy spanning generations and genres. The effect is mesmerizing, Coogler’s way of visually representing how blues music transcends the limitations imposed by history. The past, present, and future converge in an electrifying celebration of Black creativity, joy, and pain.

Yet Coogler’s vision isn’t purely celebratory; it’s tinged with the weight of responsibility. Sammie is attacked by religious traditionalists who condemn his music as “the devil’s song,” while the vampires lurk, ready to commodity his brilliance. The struggle isn’t only against supernatural forces but societal ones: racism, religious dogma, and commercialization. Here Coogler makes clear his central question: who really owns this music, and what happens when it’s taken out of its authentic context?

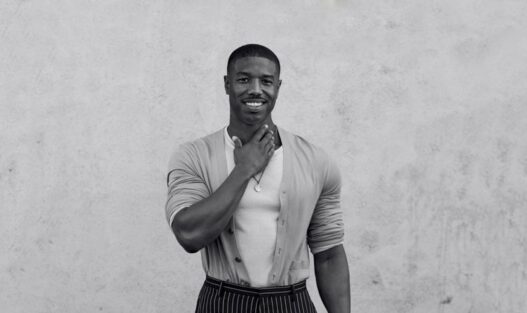

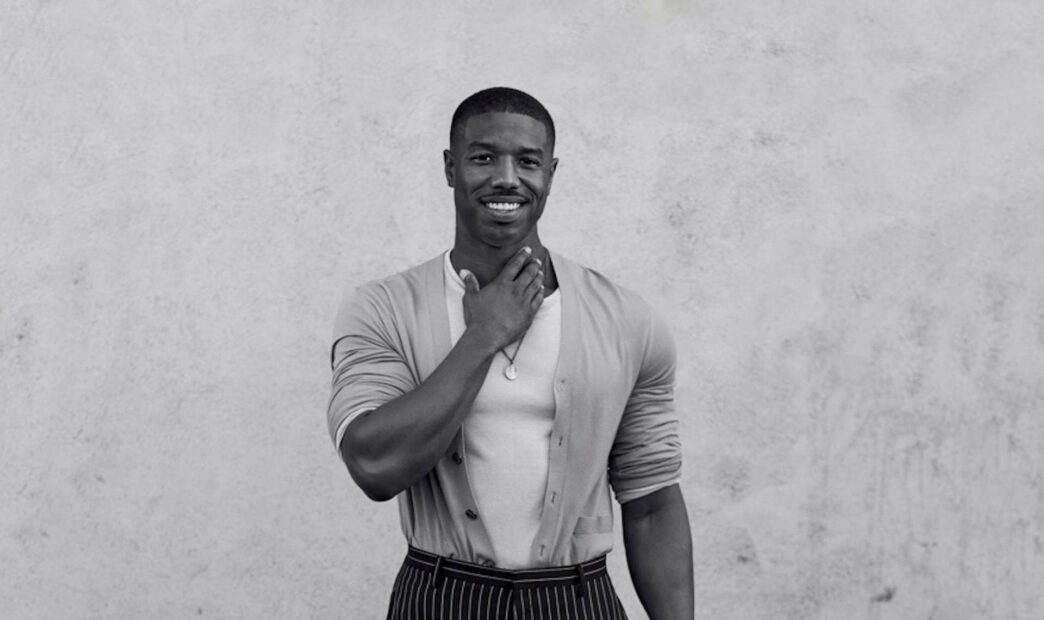

Michael B. Jordan anchors the film with dual roles that showcase his impressive range. Smoke is measured and restrained, Stack reckless and charismatic; both convincingly brought to life without overshadowing each other. The twins’ complicated dynamic embodies the film’s tension between authenticity and temptation. Stack, seduced by the vampires’ promises of immortality, ultimately succumbs to their influence, while Smoke fights desperately to preserve their original vision. It’s a testament to Jordan’s ability to portray both roles with depth and nuance, keeping the emotional stakes high.

But the film isn’t flawless. The vampire metaphor sometimes feels heavy-handed, and Coogler’s expansive ambitions occasionally outpace the film’s structure, leaving subplots unresolved and symbolism overstated. Yet the emotional and cultural resonance of the story largely compensates for these flaws. Coogler’s daring, whether it succeeds or stumbles, remains thrilling.

Ultimately, Sinners thrives not because it neatly resolves its themes, but because it fully embraces the messy, unresolved chaos of art itself. Like the best blues songs—or the greatest Metallica anthems—the film is built on contradiction and complexity, leaving audiences to wrestle with its potent mix of spectacle, symbolism, and sonic energy. Coogler’s latest isn’t simply a genre mash-up; it’s an earnest exploration of how music can be a weapon, a sacrament, or both.

By the film’s climax, it’s clear Coogler isn’t just telling a story about vampires and blues. He’s making a larger point about the cyclical nature of artistic exploitation—and resistance. This is a blues story, yes, but it’s also the story of rock ‘n’ roll, hip-hop, jazz, and every Black musical form that’s ever been co-opted by mainstream culture. Coogler dramatizes what we stand to lose—and gain—in the constant negotiation between authenticity and appropriation.

In the end, the greatest strength of Sinners is that it refuses easy answers. Like the musicians it honors, it prefers the uneasy freedom of improvisation. If you leave Coogler’s operatic Southern Gothic vampire blues fable unsettled and stirred—that’s exactly how he wants it.