Miley Cyrus’s career doesn’t follow a carefully curated arc so much as it hurtles forward, propelled by a relentless drive for reinvention. Child star, provocateur, country crooner, glam-rock rebel—each new persona complicates our understanding of who she is. On Something Beautiful, her ninth studio album, Cyrus finally slows down, turns inward, and allows herself a reckoning with the chaos she’s long embraced.

Still, this isn’t a quiet introspection. Something Beautiful, described by Cyrus as a conceptual “pop opera,” unfolds as a vivid sequence of genre-shifting vignettes, loosely inspired by Pink Floyd’s The Wall. But where The Wall leans into alienation, Cyrus charts a path through self-inquiry toward something more cohesive—if not resolved, then at least honest. The album stretches wide, but its focus remains tightly personal.

At its center is Cyrus’s voice: weathered, expressive, unmistakable. She recently revealed a diagnosis of Reinke’s edema, a condition that contributes to the gravel in her tone. What might once have been seen as a limitation is now a defining strength. On “More to Lose,” the album’s aching centerpiece, she delivers each line with a careful weariness. The rasp carries its own history, grounding the album’s emotional charge in something lived-in and true.

Throughout the record, beauty emerges not as polish but as something cracked and complicated. Cyrus doesn’t chase resolution. She allows contradictions to coexist. “Easy Lover” plays like a sultry throwback, full of rhythmic ease, while “End of the World” channels disco euphoria to stave off despair. Elsewhere, “Every Girl You’ve Ever Loved” swirls with vulnerability inside a dance floor pulse. These are songs that refuse to settle into a single tone, resisting simplicity in favor of texture.

Her transformations over the years—so often written off as calculated or erratic—are re-framed here as survival tactics. In a fame economy that punishes stasis, Cyrus has kept herself creatively afloat by shapeshifting. If earlier eras felt performative, Something Beautiful feels like a work of control, not in the sense of image management, but in reclaiming authorship. The personas collapse into one another, and the voice that emerges is hers alone.

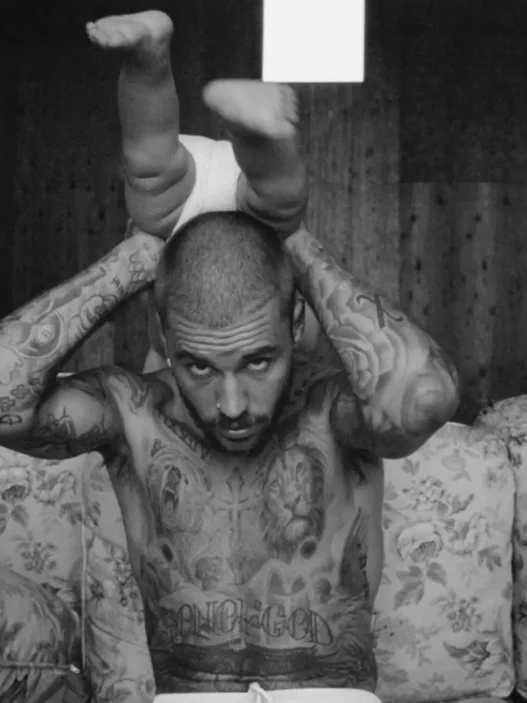

The album’s visual counterpart, premiering at the Tribeca Film Festival, adds yet another layer. Drawing on fashion’s theatricality—archival Mugler and Bob Mackie included—Cyrus uses costume not as disguise but as a storytelling device. The visuals extend the album’s themes of identity and expression, underscoring the idea that performance and truth aren’t opposites, but companions.

Still, for all its cinematic ambition, Something Beautiful doesn’t overreach. It never feels like an effort to impress. If anything, it’s a record that trusts its audience, eschewing trend-chasing in favor of emotional coherence. On “Reborn,” Cyrus sings, “Kill my ego, let’s be reborn”—a lyric that’s less about reinvention than about surrender. Not to an industry, but to herself.

In the end, Something Beautiful doesn’t declare a new era so much as it weaves the previous ones into a fuller picture. It doesn’t discard the past; it honors it. After years of chasing freedom through transformation, Cyrus stands still—and somehow, that stillness feels like the bravest move yet.