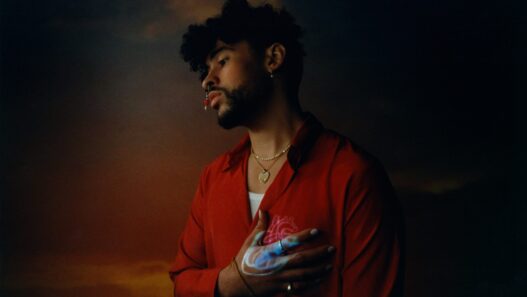

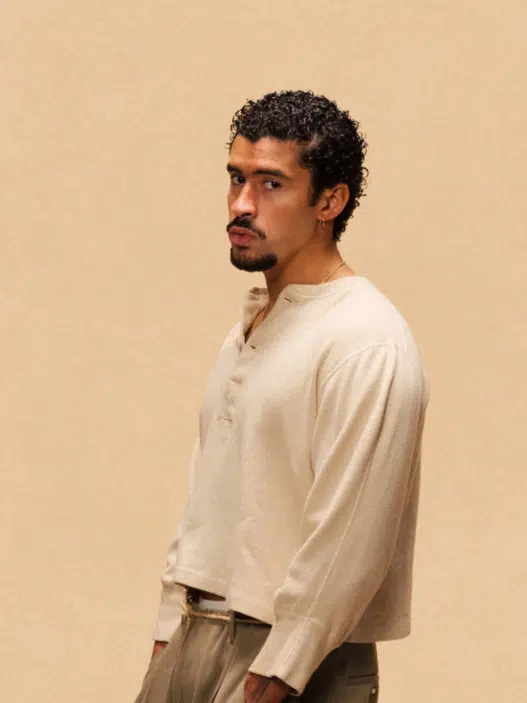

Bad Bunny has been tapped to headline the 2026 Super Bowl Halftime Show, and in announcing it he described the moment as a dedication “for my people, my culture, and our history.”

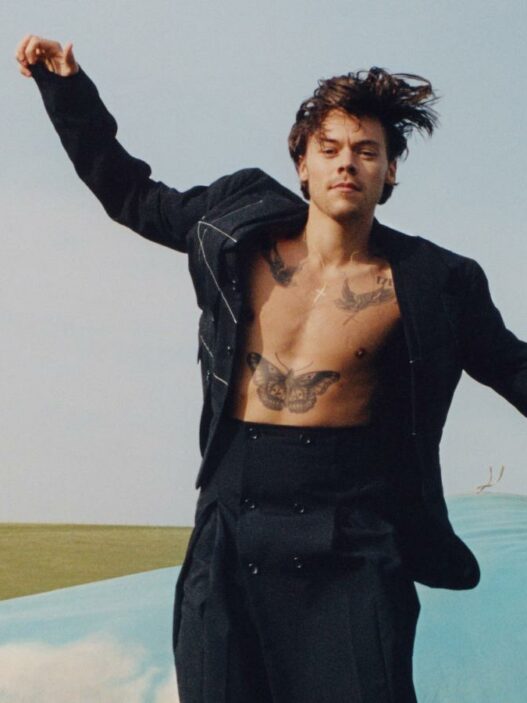

The move comes on the heels of last year’s Kendrick Lamar performance, a halftime show steeped in political symbolism and cultural provocation. Lamar used his set not just to perform hits but to stage a statement—folding choreography and visuals around songs like “Alright” and “HUMBLE.” to evoke tensions about race, power and national myth. It drew both acclaim and backlash, with some critics celebrating the reminder that Black culture is American culture and others accusing him of politicizing an entertainment spectacle.

Bad Bunny’s own catalogue suggests a different but equally potent kind of identity claim. Tracks like “El Apagón” and “Yo Perreo Sola” are love letters to Puerto Rico’s pride and nightlife, while newer songs like “ALAMBRE PúA” and “BAILE INoLVIDABLE” lean into resilience, diaspora and generational struggle. If those songs or their themes surface in his halftime show, the performance could become less a straightforward party and more a vibrant statement of belonging. But could the same tensions emerge again—will he layer political critique, or stay in celebratory mode? When artists highlight their culture, critics sometimes respond with questions of exclusion: “Why not ‘our’ culture?” But “our culture” in America is fragmented. There is no single monolithic culture that speaks to everyone. The paradox is that pop music has long encoded white cultural norms—suburban themes, universal love songs, and certain moral tropes—without framing them as identity statements.

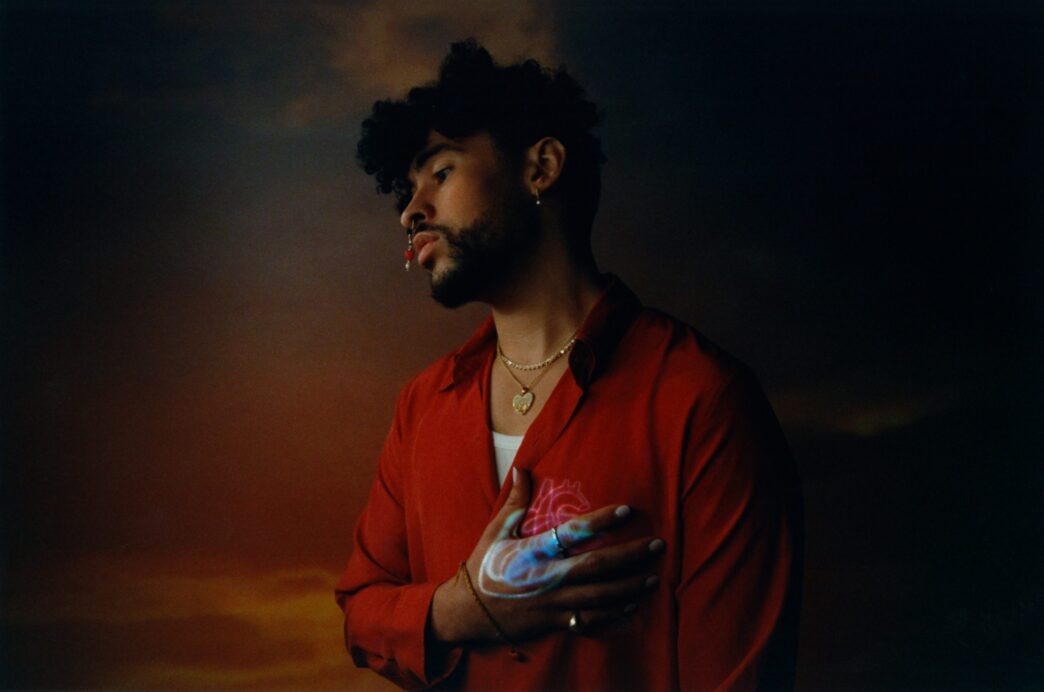

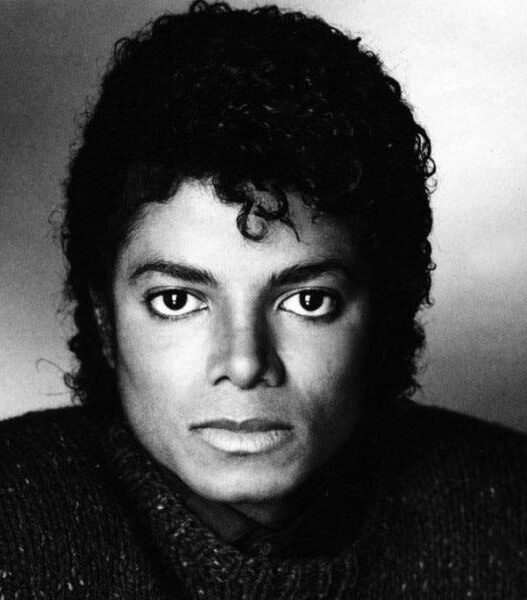

Artists like Bruce Springsteen in “Born in the U.S.A.” or Tom Petty in “American Girl” have celebrated working-class or small-town life in ways that implicitly center a particular cultural vision. More recently, singer-songwriters like Brandi Carlile weaving queer rural narratives into Americana, or Hozier taking Irish folk-soul into global protest anthems like “Nina Cried Power,” show that even in rock and indie spaces, culture and politics can surface—but they’re still rarely packaged as explicit identity statements on a mass-pop platform. By contrast, Bad Bunny, Lamar, and others now speak their identities out loud, disrupting what was once silent normativity.

That disruption carries risk. Listeners who feel excluded may tune out or resist. Audiences might view the work as niche rather than universal. Political statements can alienate sponsors or broadcasters, as seen in the complaints and social-media backlash around Lamar’s halftime show. Yet the rewards are equally compelling. Identity-rooted work can reclaim space, deepen resonance with marginalized listeners, and expand the mainstream’s frame. A reggaetón beat or the pulse of “ALAMBRE PúA” can excite someone unfamiliar with Puerto Rican slang; a rap verse about injustice may resonate even with someone who doesn’t share those lived conditions. If done artfully, such performances can invite curiosity rather than alienation.

So is there a point where both “my culture” and “our culture” can be celebrated? Perhaps it depends on artists who take risks to speak both inward and outward—who say, this is me, and I invite you in. A song can root in a specific dialect, a dance form, a memory, yet carry hooks or references that reach across difference. In the end, the trajectory we’re watching is neither wholly promising nor doomed. Bad Bunny’s performance may be a turning point—or a moment of spectacle. The question is whether it builds bridges or highlights fissures. What do you think?

Will the next halftime show bring us closer—or show us how far apart we still are?

A version of this story appears in the Winter issue of Groovevolt Magazine.